Introduction

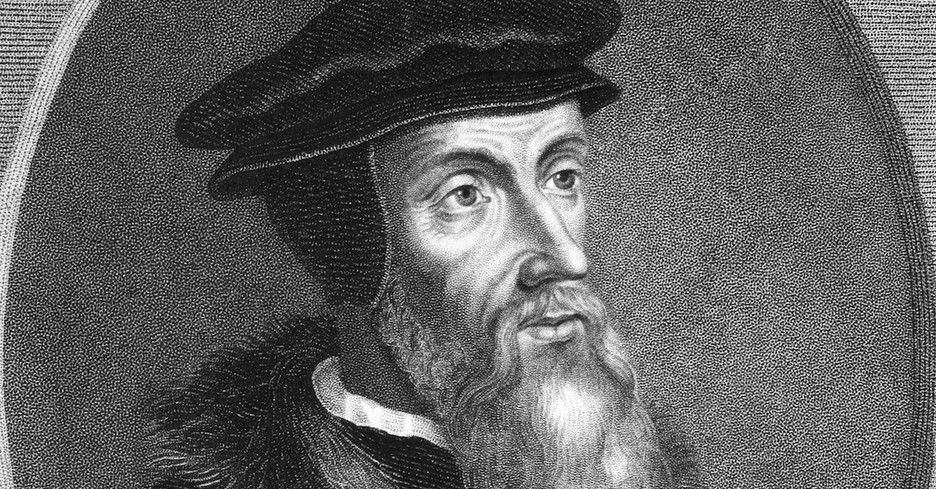

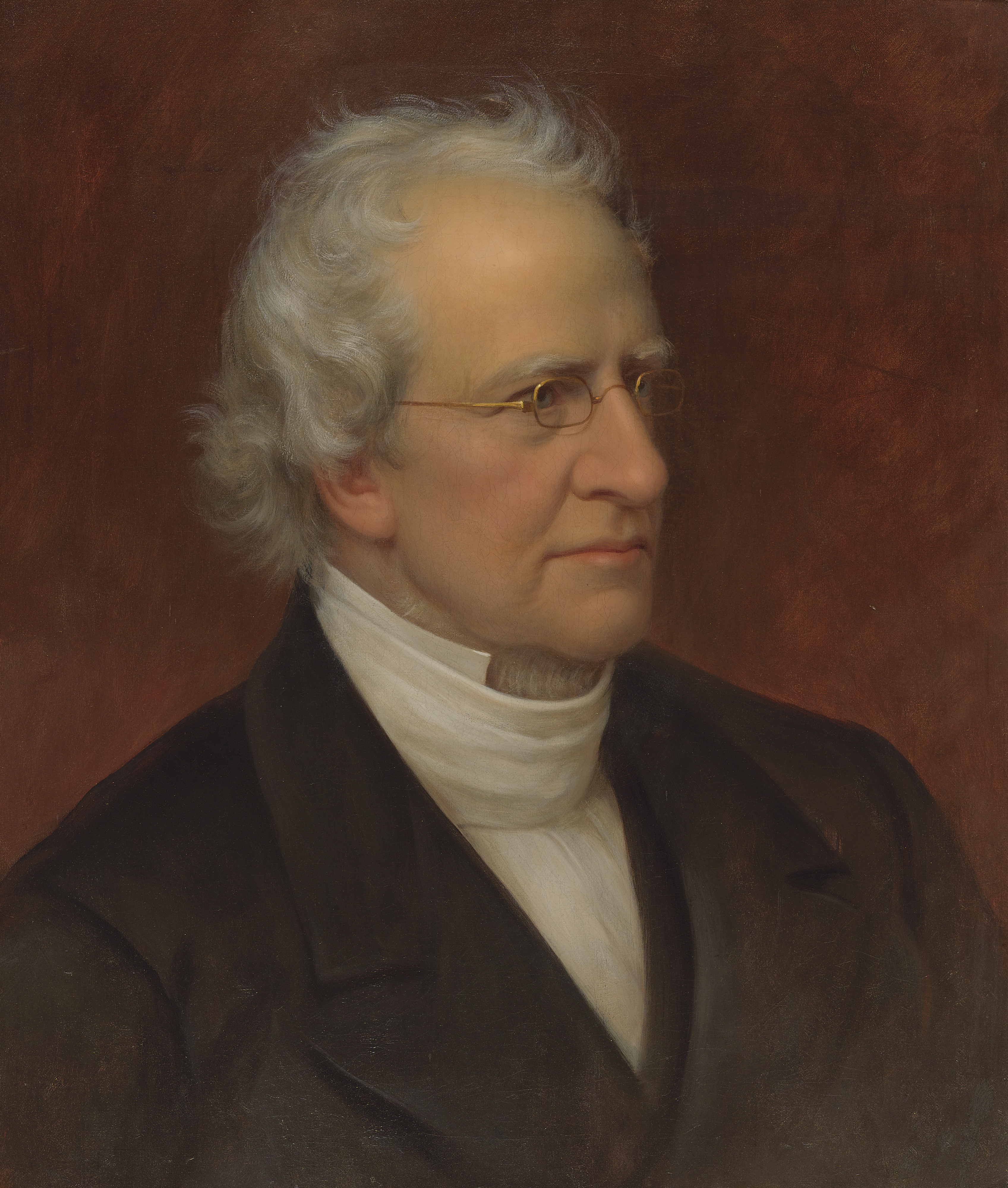

About the Author

James L. Crenshaw is a distinguished scholar and author, particularly known for his work in Old Testament wisdom literature. He served as the Robert L. Flowers Professor of Old Testament at Duke University’s Divinity School from 1987 to 2008 and has been recognized as one of the leading interpreters of wisdom literature in the Bible. He is one of the world’s leading scholars in Old Testament Wisdom literature.

Course Information

Institution: African Institute for International Studies Theological Seminary

Professor: Dr. Esckinder Tadesse

Course Name: Guided Reading and Research in Biblical Studies area

Summary of Contents

I. Spreading the Blame Around

This section discusses various responses to the problem of evil, such as atheistic answers, alternative gods, and the concept of a demon at work.

1. The Atheistic Answer: Abandoning the Quest

This chapter sets the stage for the book’s exploration of the problem of evil and the various biblical responses to this enduring theological dilemma. It mainly delves into the biblical perspective on atheism and the practical implications of denying God’s existence.

- Practical Atheism: The chapter discusses the concept of ‘practical atheism’ found in biblical literature, particularly in Psalms, where the fool (nabal) is said to deny God’s existence in his heart. This denial leads to moral decay and societal degradation.

- Divine Inactivity: It explores the puzzling nature of divine inactivity in the face of evil. The psalmist questions why God does not intervene to stop the wicked, suggesting that divine aloofness might encourage lawlessness.

- Human Depravity: The chapter also touches on the theme of human depravity, with the assertion that no one is righteous or seeks after God, reflecting a dark view of humanity’s moral state.

- Theodicy and Skepticism: Crenshaw examines theodicy—the defense of God’s goodness despite the presence of evil—in the context of biblical texts. He contrasts this with modern skepticism, which often arises from witnessing or experiencing suffering and injustice.

2. Alternative Gods: Falling back on a Convenient Worldview

Discusses the shift from polytheism to monotheism and its implications for theodicy, the defense of God’s goodness in the face of evil.

- Polytheistic Context: The chapter begins by setting the stage in a world where belief in multiple gods was common. It explains how ancient societies attributed different aspects of life and morality to various deities.

- Psalm 82: The focus then shifts to Psalm 82, where the author presents a divine assembly with God (Elohim) standing in judgment over other gods (elohim). The psalmist accuses these gods of failing to administer justice, leading to their condemnation and mortality.

- Theodicy Challenge: With the rise of ethical monotheism, the chapter highlights the challenge of explaining the presence of evil without the convenience of blaming multiple gods. The singular God must now account for both good and evil.

- Divine Justice: The chapter concludes with the psalmist’s plea for the one true God to arise and judge the earth, emphasizing the ongoing struggle for justice and the hope placed in God’s integrity.

3. A Demon at Work: Letting Benevolence Slip

This chapter is part of a broader discussion on the nature of God and the problem of evil in the biblical context. It discusses the emergence of the figure of Satan in the biblical narrative and its implications for theodicy.

- Emergence of Satan: The chapter discusses how the figure of Satan evolves from a mere adversary in the Hebrew Bible to a powerful entity in later Jewish and Christian texts.

- Divine Responsibility: It examines the notion that God’s ultimate control over Satan does not absolve God from responsibility for evil.

- Biblical Narratives: The chapter analyzes stories like the binding of Isaac and the trials of Job to explore the complex portrayal of God’s character.

- Human Freedom: It suggests that the introduction of Satan as a character may be an attempt to shift the blame for evil away from God, highlighting the tension between divine omnipotence and human freedom.

II. Redefining God

It delves into how the understanding of God’s power and knowledge can be redefined, considering human freedom, the reconciliation of justice with mercy, and the idea of God’s disciplinary procedures.

4. Limited Power and Knowledge: Accentuating Human Freedom

Discusses the concept of divine self-limitation in the context of human freedom.

- Divine Self-Limitation: The chapter explores the idea that God has intentionally limited His own power and knowledge to allow for human freedom. This self-imposed constraint is seen as a necessary condition for a genuine relationship between God and humans.

- Human Freedom: It emphasizes the importance of human free will and the ability to make choices without divine interference. The chapter suggests that this freedom is a fundamental aspect of human dignity and moral responsibility.

- Divine Vulnerability: The narrative suggests that by granting humans freedom, God becomes vulnerable to human choices. This vulnerability is portrayed as an intrinsic part of a loving and intimate relationship with humanity.

- Theodicy and Justice: The chapter also touches on theodicy, the defense of God’s goodness in the face of the existence of evil, and how human freedom plays a role in understanding divine justice and mercy.

5. Split Personality: Reconciling Justice with Mercy

This chapter is pivotal in understanding the biblical portrayal of God’s nature and the ongoing theological debate about the coexistence of justice and mercy in the divine realm.

- Divine Dilemma: The chapter explores the tension between God’s justice and mercy, highlighting the difficulty in harmonizing these seemingly opposing qualities within the divine character.

- Biblical Texts: It examines various biblical texts that reflect this struggle, particularly focusing on Exodus 34:6-7, which presents God as both forgiving and punitive.

- Theological Insights: Crenshaw discusses the implications of God’s dual nature for human understanding and religious practice, questioning how a deity can embody both strict justice and compassionate mercy.

- Human Struggle: The chapter also considers the human response to this divine conflict, suggesting that the balance of justice and mercy is a goal that societies strive for but find challenging to achieve.

6. A Disciplinary Procedure: Stimulating Growth in Virtue

Explores the concept of divine discipline as a means for moral and spiritual growth. It covers the nuanced understanding of suffering and its potential role in the divine plan for human development, while also addressing the complexities and challenges of this viewpoint.

- Divine Pedagogy: The chapter discusses how adversity and trials are seen as part of God’s teaching method, aimed at developing character and virtue in individuals.

- Biblical Examples: It examines biblical texts that depict God as a teacher or parent who disciplines their children for their own good, drawing parallels to human experiences of learning through hardship.

- Philosophical Insights: The author integrates philosophical ideas, suggesting that the universe’s opposing forces of good and evil balance each other, and that inner psychological stress can act as a form of punishment and catalyst for growth.

- Critique of Discipline: The chapter acknowledges the limitations of viewing suffering as solely disciplinary, recognizing that excessive or unjust suffering cannot be reconciled with this perspective.

7. Punishment for Sin: Blaming the Victim

The chapter critically analyzes the simplistic connection between sin and suffering and highlights the psychological need for order that underlies this belief. It also addresses the problematic nature of this response to evil, as it can lead to unjust conclusions about guilt and innocence.

- Sin and Punishment: The chapter discusses the assumption that the universe operates on a principle of justice, where good deeds are rewarded and sins are punished.

- Biblical Examples: It examines biblical narratives, such as the story of Job and the man born blind from the Gospel of John, to illustrate the flaws in attributing suffering solely to personal sin.

- Prophetic Indictment: The prophets, including Ezekiel, are cited as attributing the downfall of Israel to the nation’s collective sin, reinforcing the idea of divine retribution.

- Theodicy in Historiography: The chapter also looks at how Israelite historiography interprets national disasters as divine punishment for the people’s failure to obey God’s commandments.

III. Shifting to the Human Scene

The focus shifts to the human perspective on suffering, including suffering as atonement, justice deferred, the mystery of suffering, and questioning the problem itself.

8. Suffering as Atonement: Making the Most of a Bad Thing

This chapter provides a nuanced view of suffering, suggesting that it can have a meaningful role in the divine plan and human experience.

- Atonement Concept: The chapter examines the notion that suffering can be redemptive, atoning for sin and leading to spiritual purification.

- Biblical Examples: It discusses examples from the Bible where suffering is portrayed as having atoning value, such as in the case of sacrificial rituals.

- Jesus’ Sacrifice: The New Testament idea of Jesus’ suffering and death as a means of atonement for humanity’s sins is analyzed in depth.

- Theodicy and Redemption: The chapter considers how this concept of redemptive suffering fits into the broader discussion of theodicy, offering a perspective that sees value in suffering beyond mere punishment.

9. Justice Deferred: Banking on Life beyond the Grave

This chapter examines how the seeds of belief in an afterlife and resurrection germinated from a deep sense of communion with God and the conviction of God’s unlimited power, catalyzed by the persecution of the righteous. It contrasts this with the persistent traditional view that death is the end, showing the tension between old and new beliefs within Judaism.

- Dostoyevsky’s Quote: The chapter opens with a quote from Fyodor Dostoyevsky, “If there is no immortality, all is permitted,” suggesting that without immortality, moral boundaries may not hold.

- Scholarly Pursuits: It discusses the irony that more is written about topics that are less known, such as the afterlife, and acknowledges the limitations of human knowledge on the subject.

- Resurrection and Immortality: The chapter delves into the development of Jewish beliefs about resurrection and immortality, particularly in response to theodicy and persecution.

- Resistance to Belief: It also covers the resistance to the belief in resurrection within Jewish tradition, citing views from texts like Job and Ecclesiastes that emphasize the finality of death.

10. Mystery: Appealing to Human Ignorance

The chapter delves into the paradox of a God who is both self-revealing and yet remains hidden from human understanding. It discusses how the Bible often speaks of God as an active participant in human affairs, with a seemingly transparent nature and activity. However, it also acknowledges that God’s ways and thoughts are ultimately inaccessible to humans.

- Paradox of Knowledge: The chapter explores the tension between the belief that God can be intimately known and the frequent biblical warnings that God dwells in darkness, beyond human sight.

- Divine Activity: It examines the portrayal of God’s role in the history of Israel and Judah, where divine actions are described as leading or disciplining the chosen people.

- Limits of Human Understanding: The chapter emphasizes that while the Bible gives the impression of describing reality, the knowledge of God it conveys is not subject to rational examination.

- The Mystery of God: It concludes that all knowledge of God and His ways is partial, suggesting that the biblical characterization of YHWH may only be partially accurate, and that the ultimate questions about God remain surrounded by mystery.

11. Disinterested Righteousness: Questioning the Problem

Provides the complexities of human understanding of God and the limitations of human knowledge in theological discourse.

- Anthropocentric Theology: The chapter discusses how human perceptions of God are influenced by anthropocentric tendencies, suggesting that the biblical depiction of God carries the same limitations as human knowledge.

- Literary Construct: It examines the idea that the biblical portrayal of God is a literary construct, which has been reified and absolutized over time, leading to a loss of the representational character of the divine.

- Job’s Insight: The book of Job is highlighted as a text that challenges traditional views of God, emphasizing the importance of questioning and the struggle to understand divine justice.

- Theological Complexity: Crenshaw argues for a recognition of the complexity and ambiguity inherent in theological claims, advocating for a humble approach to understanding the divine.

Reflection/Reaction

This book is a thought-provoking work that engages with ancient and modern perspectives on theodicy, offering insights into how different cultures have grappled with questions of divine justice and human suffering. It offers an excellent defense of scriptures, providing sound instructions on how to read and understand references to God’s actions. The book serves as a great guide to important literature and commentary on the problem of theodicy.

Gap

The author focuses on Western perspectives and thought. It could benefit from a more diverse range of perspectives, including non-Western and contemporary viewpoints.