Introduction

About the Author

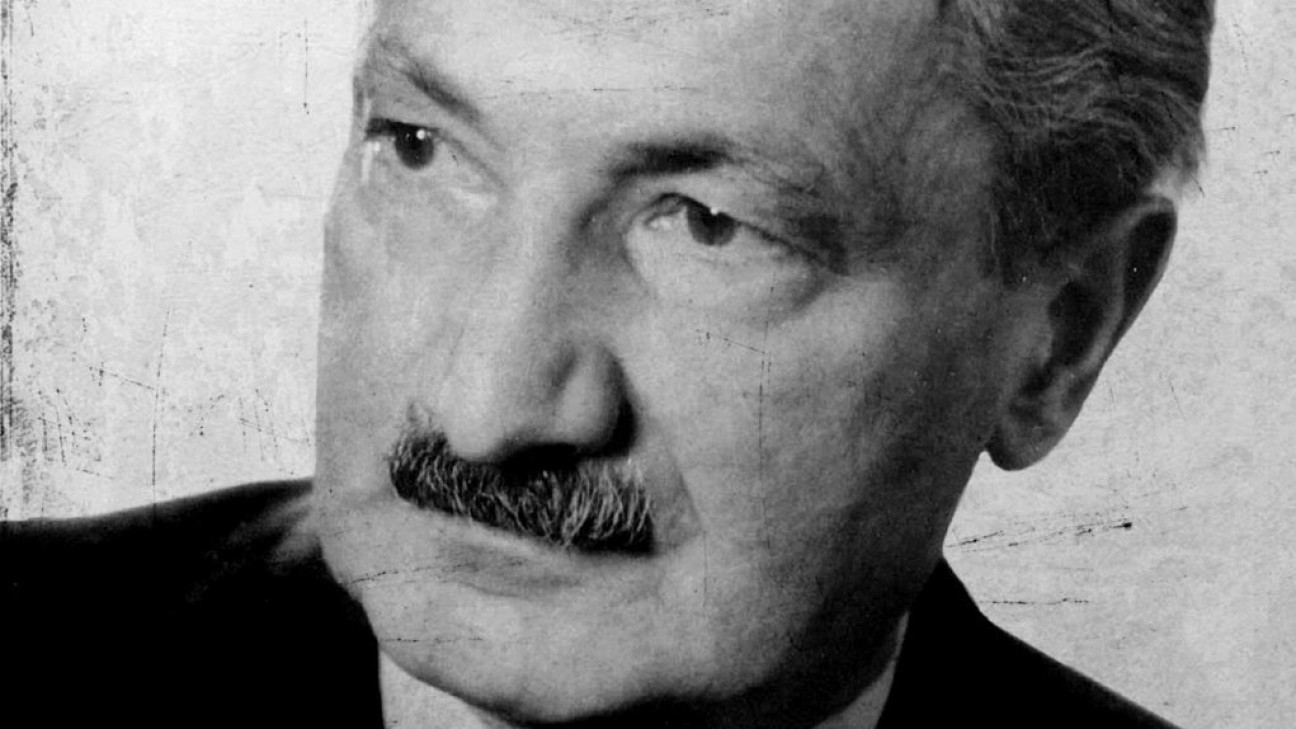

Timothy Clark’s Martin Heidegger is an intelligent, highly accessible introduction to the German philosopher’s complex intellectual trajectory. In its focus on Heidegger’s engagement with art and language, Clark’s book will be of particular interest to students of aesthetics, literature, and theory. Michael Eskin, Columbia University, notes, “Timothy Clark’s Martin Heidegger is an intelligent, highly accessible introduction to the German philosopher’s complex intellectual trajectory.” Jonathan Ree, Middlesex University, adds, “Heidegger was a uniquely gifted practitioner of the difficult art of reading. But his achievements have been overlooked or drastically misunderstood by mainstream literary theorists and critics. Timothy Clark’s accessible, neat and reliable introduction goes a long way towards setting the record straight.” Timothy Clark is a specialist in Romantic and post-Romantic poetics, based at Durham University. He is co-editor of the Oxford Literary Review and author of Derrida, Heidegger, Blanchot: Sources of Derrida’s Notion and Practice of Literature (1992) and The Theory of Inspiration (2000). Routledge Critical Thinkers is a series of accessible introductions to key figures in contemporary critical thought.

Methodology of the Author

Critical thinking and historical philosophical

Summary of Contents (Excellence)

Why Heidegger?

Martin Heidegger is the hidden master of modern thought. Heidegger’s work touches the deepest, usually unconsidered assumptions of all work of thought, forming a reassessment of the drive to knowledge itself. In the second half of the twentieth century, it was often under Heidegger’s direct or indirect influence that the traditional view that intellectual and scientific inquiry, the search for truth, is inherently disinterested, or even critical of unwarranted forms of authority, gave way to arguments that the drive to know is often compromised by elements of domination and control. Heidegger died in 1976 at the age of eighty-six, and his work has become deeply reactionary in the proper, not necessarily condemning sense of the word. Heidegger was a philosopher who gave supreme importance to some poetic texts. Hans Georg Gadamer (1900-), who was to become Heidegger’s most famous student, remembers the immense shock of first encountering Heidegger’s teaching in the 1920s: Heidegger’s thinking embraced not just the philosophical and social crisis of Germany at this time, but became a powerful reassessment of the most basic values and assumptions of Western civilization since ancient Greece. He turned from being trained as a cleric to the sciences and mathematics and then to philosophy, becoming the star pupil and then main follower of Edmund Husserl (1859-1938), founder of the school known as ‘phenomenology’. Heidegger became Husserl’s successor, living the uneventful, slightly self-enclosed life of a professor of philosophy at Freiburg. In 1933, a few months after it had come to power in Germany, Heidegger joined the Nazi party. From 1933 to 1934 he gave the Nazis his support as Rector of Freiburg University. So readers of Heidegger have had to hold in their minds two almost irreconcilable facts: that Heidegger is widely regarded as the greatest philosopher of the twentieth century; that, for an uncertain time, he was a supporter of the Nazis.

The Limits of the Theoretical

Heidegger is often acknowledged as the most decisive and most influential thinker of the second half of the twentieth century. ‘Do we in our time have an answer to the question of what we really mean by the word “being”? Not at all’ (BT: 19). Such a stance on things, on being, interrogates them with a view to what can be construed as universally true, perpetually extant/present as an object of contemplation for the intellect. This is the supposedly ‘true’ world, perceivable with difficulty by the mind alone, as opposed to the ‘lesser’ immediate world of sensations, passions, and interests in which we find ourselves.

The Pre-Theoretical Conditions of Theory

Since Socrates and Plato, philosophers and later scientists have assumed that to have a rationally grounded knowledge of something means to have a transparent and self-consistent formulation of its underlying principles.

Truth as Correctness and Truth as Unconcealment

Since Aristotle, truth has been taken to name, simply, the relation of a judgment or proposition to reality. Heidegger is not denying then ‘that truth exists, nor is he arguing that natural science has no more than the status of one cultural practice amongst others, or that all systems of thought or interpretations of life are “merely relative” etc. or other clichés of so-called postmodernism. But he is arguing that all theories of human life are made possible by a pre-theoretical relation to being that must always be assumed but which could never be fully conceptualized. Heidegger does not offer a new systematic theory of the world, according to the engineering model of understanding. He works to render explicit what we already understand reflectively, invisible merely because so deeply taken for granted, even by centuries of philosophers and scientists.

Deep History (Geschichte)

Human beings are essentially historical. They are born into an environment already formed by multiple layers of interpretation and tradition, even down to the most seemingly immediate sense of things and of the ‘I’ that perceives and thinks them. The ‘history of being’ is the context for all Heidegger’s thinking about art, literature, and cultural debate. The word ‘history’ (Geschichte) here is as specific to Heidegger as is the word ‘being’. Heidegger is exploiting the fact that German has two words for history, ‘Historie’ and ‘Geschichte.’ Historie names the familiar sense of history as the study and narrating of the past, as conceived by Geschichte, on the other hand, names something less familiar and more profound. Historical in this way are (not ‘were’) those fundamental ways of thinking and being in which Western humanity has dwelled and understood itself since ancient Greece. Plato’s and Aristotle’s thinking still bore the traces of older, pre-metaphysical ways of thinking.

What Happens in Deep History (Geschichte)?

In Heidegger’s history of being, perhaps only three events emerge as truly ‘historical’ (geschichtlich) in the guise of a change in the fundamental sense of the world, in the ‘essence of truth’. First is the translation of the Greek world into Roman Latin. Finally, there is the emergence of the modern metaphysics and science in the seventeenth century, the dominance of questions of Phrases Heidegger uses such as ‘being withdraws’ or ‘history of being’ make it sound as if ‘being’ were some kind of inscrutable non-human agent, even God, but this is an accident of language. The overall shifting of epochs is not liable to human control, nor can there be any sort of logic of the transitions from one epoch to another, nor, certainly, can they be said to progress.

The Epoch of Techno-Science

For Heidegger, the principle names the imperative that directs our epoch of technoscience. For all its seeming dethronement of the importance of ‘man’, with, for example, the removal of the earth from the center of the universe, or the humiliation of Darwin’s theory of evolution, modern science at heart exalts human rationality to a degree never before conceived. Modern historiography and modern science go hand in hand with the principle of reason: For Heidegger, technology in the familiar sense is an effect of that general structure of representing the world which has come to govern the epoch in which we live.

‘The Origin of the Work of Art’

‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, described as simply ‘the most radical transmutation of aesthetics’, or the philosophy of art, ‘since the Greeks’ At issue throughout ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’ and not fully resolved by the end is the nature and potential of artworks in the time of the dominance of technological thinking. Heidegger’s essay is in debate with the claim of his great predecessor in philosophy, G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831), made in the 1820s, that ‘art is and remains for us, on the side of its highest destiny, a thing of the past’ Art, for Heidegger, is finite and something that can die. Dying, it can lose its power of disclosure and appear merely as an attractive object to be hung in a museum, or toured on holiday; or it may be reduced to a small element of the education system or appropriated as a cultural asset, as ‘heritage’. So, the very possibility of effective art in modern society is questionable for Heidegger. Is it techno-science, not art, that is now fundamental to the West’s outlook on everything? Heidegger’s essay rejects a view of art so deeply rooted that it is often passed over as self-evident: namely that the artwork is to be understood under the category of representation, or imitation (mimesis), as when we say that a play or a novel ‘re-presents’ or ‘mirrors’ a particular society or that it expresses or stands for the opinions or emotions of its author. Great art, for Heidegger, is involved with truth, not in the sense of the conformity of a proposition to a given state of affairs, but as aletheia, unconcealment. Blanchot also follows Heidegger’s rejection of representationalist theories of art. World and earth are essentially different from one another and yet cannot be separated. It enters into a subtle and elusive relationship with that material, so that the matter—rock, air, colours—is both affirmed and yet remains separate in its otherness. Earth in relation to the work of art is the material out of which it is made, and a literary work is made from language. But Heidegger also talks of the ‘naming power of language’, its power of referring to things. Heidegger turns instead to the way great art is engaged with issues of truth, making a fundamental claim upon us as to the nature of our existence. Great art is capable of setting forth and sustaining the most basic sense of things in a people’s life. So art, for Heidegger, is always an inherently communal affair, putting at issue a society’s modes of perception. The work’s truth is always offset (like light and shade) by the depth and resistance of what Heidegger calls its ‘earth’ quality, as opposed to the way it projects a ‘world’.

The Death of Art?

The death of art is an issue bound up with the way art is received in the modern epoch. Heidegger is preeminently the thinker of the decline and possible death of art. Heidegger also compares the disclosive power of art to that of ‘essential sacrifice’, an obscure reference, apparently, to the Crucifixion of Christ as a world-altering event. As we have seen, Heidegger is preeminently the thinker of the decline and possible death of art. Heidegger argues that the work of art has a finite life-span. For Heidegger art dies once its world-disclosing is covered over with attitudes that take it merely as a source of aesthetic experience, or as a cultural or historical artefact or, one must add, when it becomes valued oneself entirely as an object of critical study in universities or for public display in museums. Art’s death is not instantaneous and is still in process. For Heidegger such dying is perhaps what modern art is. The Greek Temple was an instance of pre-modern art, opening the question of whether modern art can ever have quite the same power.

Language, Tradition, and the Craft of Thinking

Heidegger’s thinking on language is as distinctive as any other aspect of his work. It is an instrument whereby we represent things or thoughts to ourselves and to each other, a medium of communication. First, speaking in conversation is as much a matter of listening as it is of talking. In the current view, language is held to be a kind of communication. It serves for verbal exchange and agreement, and in general for communicating. Finally, we turned to the way in which Heidegger’s rejection of the instrumentalist conception of language led to his various provisional experiments with new modes of writing and practicing philosophy. These included his use of the dialogue form, his seeming ‘poems’ and the posthumously published Contributions.

Quizzical Interlude: What is a Literary Work?

After all, we distinguish good and bad performances of a work and this clearly assumes that the work and the performance are not identical things. The real work is the work as it appeared to readers at the time of its initial publication. Heidegger’s work on the poetic has been immensely influential, but not on the surface. It is contrary to the spirit of Heidegger’s thinking that it should found any school or be schematized into a technics of interpretation. Another crucial issue in ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, let us recall, was the rejection of the notion that art is a reflection or mirror of some sort. The poem is clearly about the nature and duty of the poet, but that is only superficially the issue. The work, then, is not a material thing.

Heidegger and the Poetic

Heidegger’s readings of poets have been widely if often implicitly influential, but they were never in fact primarily intended as part of the business of literary criticism, a discipline Heidegger saw as a parochial representative of the sort of thinking he was trying to challenge. Hölderlin bears the weight of all that Heidegger is trying to find redemptive in art. The reception of Heidegger’s readings of poetry has been held back by a simplistic understanding of Heidegger’s affirmation of Hölderlin’s view that poets are the real founders and determiners of human history, legislating the basic myths, assumptions, and ways of seeing that are then inhabited by others. Heidegger’s goal is a transformation of the reader’s deepest assumptions: most approaches in literary study, in other words, must be left behind. The whole point of Heidegger’s turning to poetry is to do justice to modes of being and thinking that are still not fully determined by productionist metaphysics. Heidegger’s concerns are thoroughly historical in a sense, but his concern is deep history in the sense of Geschichte. ‘Germania’, the first poem Heidegger ever treated in depth, bears out a holistic principle that recurs in all his later readings of poetry. After his controversial and abortive engagement with politics in the early days of Germany’s Nazi government, Heidegger turned to art and the poetic, above all to the German romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin.

Nazism, Poetry, and the Political

Heidegger and Nazism: the issues are so contentious, so overdetermined by contemporary intellectual politics, and some of the concerns so horrific that this is a topic about which it is probably impossible to think straight. Farias’s argument that Heidegger was a Nazi throughout his life and his work thoroughly fascist is easy to dismiss. What is incontestable is that Heidegger joined the Nazi party in May 1933 and that during 1933-4 at least his political engagement was a matter of genuine conviction and even excitement. In May 1933 Heidegger was elected by his colleagues to serve as Rector of Freiburg University. How do these issues relate to Heidegger’s thinking about art and the poetic? The writings on the poetic all postdate his Rectorship and are generally read as a reaction against it. Despite the arguments of ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, the poetic is not given its full singularity, but is still being weighed predominantly as a means of knowledge, albeit in a radically altered form. In this respect, the reading of Heidegger becomes an extreme example of the ethical dilemma of reading more generally, in any significant text. We are torn between conclusive interpretation or judgement and openness and re-reading. This intractable difficulty continues to be endured in Heidegger’s legacy.

After Heidegger

After Heidegger? Heidegger died in 1976, but we are not after Heidegger. His work engages questions at the most fundamental level imaginable about the nature of a human existence and what we have come to understand as knowledge. His thinking touches on about every field of intellectual work. So there is no ‘after’ Heidegger in the sense of something that can now be understood at a distance or put ‘back into context’—for that context is what we inhabit, the globalized, industrialized, and industrializing world whose basis is productionist metaphysics. Heidegger’s overall influence on modern thought is simply too vast to document in a book focused primarily on questions of the poetic. As well as transforming poetics, Heidegger is an unavoidable reference point in any discussion of the distinctive character of the West, of the nature of technology, of the nature of history and of historical study, of environmental ethics, of the nature and limits of science, of religion, of medicine and psychoanalysis, of the nature of Nazism, of the relation of the West and Asian thought, and so on. Heidegger has been one of the major thinkers of what we now term globalization.

Reflection

Heidegger sees the foremost task of philosophy not as the explanation of the meaning of “particular beings” but also the clarification, pronunciation, and poetic composition of a new essence of Being and in this manner of a new essence of man. Generally, I appreciate Heidegger for his efforts and influential philosophies he has done in the 20th century.

Critical Questions

- The very possibility of effective art in modern society is questionable for Heidegger.

- Is it techno-science, not art, that is now fundamental to the Ethiopian’s outlook on everything?

- How is it, in this epoch? or How is it for us?

- Heidegger is predominantly the thinker of the decline and possible death of art.

Bibliography

[Not provided in the document]